Barks Blog

Which Pavlov Is on Your Shoulder?

The trainer Bob Bailey is often quoted as saying that when one is training an animal, “Pavlov is on your shoulder.” He is reminding us that while we are training operant behaviors (sit, down, fetch, weave), there are also respondent behaviors and respondent conditioning occurring. Respondent behaviors are behaviors that are generally involuntary and that include reflexes, internal surges of hormones, and (probably) emotions.

But there’s another part that is not quoted as often. Bob Bailey also says that while Pavlov is on one of your shoulders, Skinner is on the other. (B.F. Skinner was known for exploring operant conditioning.) In his Fundamentals of Animal Training DVD, Bailey states that both fellows are always on your shoulders. Depending on what you are doing, one may shrink while the other grows in importance. (Great visual, eh?)

When we are training operantly, there are still classical associations going on. And when we are doing classical conditioning, there are operant behaviors that come along and get reinforced.

I find these mixtures fascinating and have some posts and video examples.

• In this post, I describe and show how I was using Skinner for operant behaviors but Pavlov was on my shoulder. You can see the results of good associations (food, play) with agility behaviors. I was teaching operant behaviors, but many aspects of the training (including me) got a positive dose of classical conditioning.

• In this post and video, I discuss how I performed Pavlovian conditioning. But Skinner came tagging along close behind. You can see the results of classically conditioning my dog Clara to respond favorably to another dog barking. Yes, she even drools. We can assume that her body is getting ready to ingest food. But we also see tail wagging, orientation to me (food lady), and in the end, running to me when she hears barking. Those are all operant behaviors. She was performing operant behaviors that reflected her emotional state and expedited the food delivery, and those behaviors got reinforced.

What About Fear Conditioning?

Wait, what?

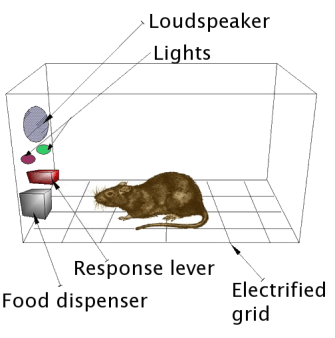

We often use classical conditioning procedures with the goal of alleviating fear. We do this by classically conditioning an appetitive response, and, via desensitization, slip it in place of the fear response. But the term “fear conditioning” means something else in the literature. It refers to using classical pairing to create a fear response to a formerly neutral stimulus. Scientists including Pavlov did this. Such experiments have been performed for decades. Animals learned that a buzzer, light, or other stimulus predicted a shock to the floor of their cage or to some apparatus. They started showing fearful behaviors and a general suppression of behavior when exposed to the predictive (conditioned) stimulus.

These pairings happen in life all the time. Some years back, a pair of Carolina wrens were nesting in a rubber bucket on my back porch, but I didn’t know it. The bucket was up on a table and one day I went to put it away. I grabbed it and a bird flew out noisily right into my face. It scared the crap out of me. Even though the startle wasn’t painful, nor was my life in danger, that’s the way I reacted. And I got leery of that bucket. I avoided moving it again until six months later in the dead of winter. Even then I touched it only after getting on a ladder to peer into it from a distance. I remained wary of the bucket for a year or two after as well. The bucket was not directly responsible for my scare. It was just a bucket. But I couldn’t shake the anxiety that got attached to it for quite a while.

Not all associations are dramatic or come from trauma. Repeated unpleasant experiences can become associated with the place they happened or the sight of the person who caused them. How about when that person who bugs you comments on Facebook? All you have to see is her name—not the content of the current remarks—to get a sinking feeling.

Back to dog training. People who train using aversive stimuli also have Pavlov on their shoulders. But trainers who use shock and prong collars, molding and body pressure, or who throw things are not generally accompanied by Nice Pavlov*. Not the one who floods the animal’s body with “let’s eat!” or “let’s play!” chemicals and causes pleasant anticipation. They get Bad Pavlov, the one associated with fear conditioning. The one who causes the animals to hunker down in fear. Here is an example of a dog who looks like Bad Pavlov is hanging around. (I have used the Do Not Link function in hopes of not adding hits to this shock training video.)

There’s nuance in reading the body language, of course. If an animal has enough training to know how to control the aversive stimulus with its behavior, it won’t necessarily look miserable. Also, you can see happy body language on an animal being trained with aversives if the activity itself is fun. Hence the dogs who are said to “get excited” when the prong collar comes out—because it predicts a walk. Disassociate the walk and you will find that the prong collar—surprise—is not intrinsically fun. In a mixed case like this, though, I envision the aversive control as a heavy weight that always has the potential to pull the dog’s emotions in a negative direction or to suppress its behavior. The dog’s happiness is despite the aversive stimulus, not because of it.

Nice Pavlov Is Not Automatic

Just as the presence of aversives doesn’t always squelch all of the pleasure out of a situation, the presence of appetitive stimuli doesn’t guarantee rainbows and unicorns. We tend to assume that if you train with positive reinforcement, you automatically get a positive conditioned emotional response. But it ain’t automatic. There are ways to mess it up.

If you are generous with reinforcement, minimize extinction frustration, and don’t frustrate or scare your dog—Nice Pavlov is probably on your shoulder. Your dog will build good associations to the training experience and to you. But what if you frustrate or scare your dog? What if you repeatedly get in your dog’s space and don’t notice that she doesn’t like that? Is Nice Pavlov going to show up and save the day just because you are using food? Probably not. You are not going to get a sweet, positive conditioned emotional response to your cues, to your training sessions, or to you if you are regularly letting aversive events creep into your training.

Here’s what it can look like if our own training session—with food—is less than fun for the dog. I’ve set the link to start the video in the middle where training of my older dog, Summer, begins. It was a moderately stressful session for her, with too many competing, slightly scary stimuli from the environment. I was also asking for stationary “leave-it” behaviors that need a lot of self-control, and I was using kibble, a low-value food. Not a great combination.

Summer was a trouper, worked hard, and although she was clearly anxious through much of the session, succeeded at what I asked of her. I wouldn’t say this session damaged our relationship or tainted training in general—we had much too strong a history of happy training. But consider this: what if every training session I ever had with her was like that? Mildly scary stuff, hard tasks, low-value treats. Even though it would still be “R+ training” I don’t think I would have built up much of a positive response to training. Nice Pavlov would not have joined us—or if he had, he would have been smaller than Bad Pavlov. (Too many dudes on our shoulders!)

The photo above shows Clara on a day in 2015 after she knew I was getting ready to trim her nails. I have always used tons of good food, and Clara had been comfortable with nail trims for quite a while. But nice Pavlov was not in sight. Clara was recovering from Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. While she had been sick, her joints had become painful, and it bothered her for her feet to be handled and nails trimmed. (I should not have trimmed them.)

Are Pavlov and Skinner All Jumbled Up?

Yes and no. Operant and respondent behaviors are both going on all the time. But I’ve also seen some trainers use it as an excuse. They say that since Pavlov and Skinner are both present, we shouldn’t get “hung up” on which one is primary. Well sure, we can’t crawl inside the animal’s body to check. But our training procedure should reflect our goal(s). And we should definitely get hung up on whether the dog is enjoying herself.

Teach Your Children Puppies Well

Positive reinforcement-based training done even moderately well comes with lovely side effects for the trainee (and also the trainer). But badly attempted R+ training that regularly lets aversives, coercion, or too much difficulty in the picture can stress out dogs. If I grab my dog’s collar to move her and I haven’t conditioned her to that, she may dodge when I grab the next time. That was aversive. If I push into her space to get her to move and she starts jumping back when I approach her, that was aversive. If I play a game with a fearful dog where they need to come closer and closer to me to get the treat and I go too fast—I am the aversive.

So take this friendly reminder from someone who has made plenty of mistakes. Yes, Pavlov is always on your shoulder. But even if we use food to train, it doesn’t mean we will automatically get a beautiful positive conditioned response to training. There are other stimuli that can creep into our training sessions that can knock the fun right out of it.

*Pavlov wasn’t actually what we would consider “nice” to dogs in this day and age, although he was likely better than many experimentalists. I’m using some rhetorical license here.

Copyright 2018 Eileen Anderson

Pavlov photo credit Wikimedia Commons. Additions in color are mine.

Skinner Box diagram credit Wikimedia Commons.

Carolina Wren photo credit Wikimedia Commons.

Photo of Clara credit Eileen Anderson