Barks Blog

How to Become a Better Animal Trainer

By Karolina Westlund Ph.D. of PPG corporate partner Illis Animal Behaviour Consulting

It took me years to realize this, but there are some approaches that really propelled my learning about animal behaviour management in general, and animal training specifically.

Here are the four tactics or concepts that I’ve found most useful:

1. LEARN FROM MANY TEACHERS

I still remember the goosebumps I got when I first came across a professional animal trainer and got to see her in action. I saw a monkey change his behavior over the course of a short training session, and I was hooked. As an ethologist interested in animal welfare, the implications were enormous – and it looked like great fun, too!

I started reading. Attending courses and training conferences, watching DVDs and discussing with like-minded people. Training animals myself. One of the greatest insights I have from these early exploratory days is this: as I learn from different people, their perspectives, theories and experience come together synergistically.

I sometimes meet people who have met influential, charismatic animal trainers, and looked no further. They follow them faithfully, put them on the proverbial pedestal and take pride in putting all others aside. These devout followers read their books, attend their seminars, and defend them vehemently if their training approach is criticized.

While this dedication is admirable in a way, it’s also disadvantageous in that even the most determined trainee won’t learn everything that their teacher knows. Also, they have no way of identifying weak points in the guru’s approach to interacting with animals, nor get the epiphany of connecting dots between different perspectives.

By having multiple teachers, many of those weak points become blindingly obvious.

Not all, because we tend to be steeped in the same views on animals, living in the same 21st century paradigm – sharing the same cultural fog (a favourite topic of behaviour analyst Susan Friedman), as it were. At the very least, by having many teachers and sources of inspiration, you start seeing where different trainers agree – and where they disagree.

2. LEARN FROM MANY INDIVIDUAL ANIMALS

The animals you train are your teachers, teaching you the skills needed to be a successful animal trainer. As humans, we’re creatures of habit, we’re superstitious (seeing patterns, assigning meaning and correlation where there is none) and we generalize what we learn.

I hate to shatter your illusions, but having excelled at training one individual animal does not automatically make you a good animal trainer.

I recently spent 3 months cat-sitting. Before our new guest arrived, I was confident that it was going to be a breeze: after all, I grew up with a cat who was with me for 20 years. I understood her every meow, I knew her favourite scratching places and her dislikes. On top of all that cat experience, I’d earned a Ph.D in ethology, taught university level learning theory and behaviour management.

Cat-sitting wouldn’t faze me.

Or so I thought.

Needless to say, it was a sobering experience. Much to my surprise, getting to know a new cat took some hard work, mostly because many of my expectations of living-with-a-cat weren’t met.

This cat doesn’t like to be touched, but my childhood friend loved being petted.

This cat doesn’t flinch when my kids holler and run about; my old kitty would have run off to hide.

This cat talks to me, and I don’t quite know what she’s saying.

Animal training is all about flexibility. It’s changing your own behaviour so that the animal will do the same.

If you’re only training one individual animal, you’re not stretching your wings enough and it’s my warmest recommendation that you look around for some other trainee.

Which, incidentally, brings us to the next topic.

3. LEARN FROM SEVERAL ANIMAL SPECIES

Did you ever train a cat? Many cats will lose interest in a training session very quickly: the first clicker training session that I attempted with my feline guest was less than a minute and, if I’m not mistaken, involved 6 or 7 repetitions.

Then she walked off, tail high.

In contrast, training undomesticated animals such as primates, the first training sessions often involve gaining trust. Addressing safety issues, avoiding eye contact, moving slowly, finding the best treats to encourage cooperation. Forget the clicker, get them to take food from you.

Cooperation was not a problem the first time I trained a dog. Nevertheless, I managed to mess it up completely. The small Papillon gave eager eye contact, started offering her whole repertoire of tricks, anticipating my next cue. My timing was off, my plan went out the window, she barked and danced and my fellow trainers who witnessed the sorry affair probably snickered inwardly.

Some things that influence the outcome of a training session will be the animal’s temperament and personality, the quality of the relationship, the presence of distractions and potentially aversive stimuli.

Check out my short, juicy and FREE e-book containing some of the insights I wish someone had told me early on!

If you don’t have time to work through a whole menagerie, which species is the best to learn the skills of the trade from?

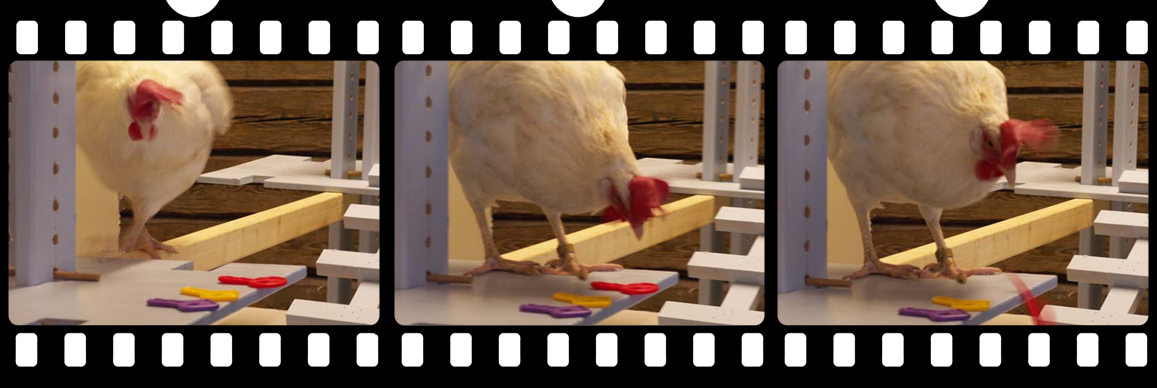

Well, Bob Bailey, one of the animal training gurus I’ve had the privilege to learn from, having trained tens of thousands of individual animals and several hundred species, suggests chickens. They’re motivated, active, not all that distractible, and their behaviour is generally not influenced by social cues from you.

Although my practical experience is but a fraction of his, I agree.

4. KEEP AN OPEN MIND

Each animal trainer has her own journey, but typically something triggers the urge to learn more about how to train animals.

Someone may see a dog agility show, get instantly fascinated and want to learn more.

Another may learn that there are other ways of weighing a bear in a zoo than darting it with a sedative.

A third may search desperately for ways of resolving the screaming habit of the new parrot.

Here’s my journey.

As an adolescent cat owner, I thought relationships were all that mattered in achieving high animal welfare, apart from the veterinary perspective.

Later, I assumed that I knew all there was to know about animal behaviour as a trained ethologist, looking at behaviour from an evolutionary view: how to set up the environment to promote natural behaviour.

Then I learned about clicker training, and practical applications of operant conditioning. It blew me away.

Then I realized that clicking and treating wouldn’t always be the best approach when training; respondent conditioning is hugely important, too. I now consider counterconditioning one of the five most important tools in the animal trainer’s tool box.

Not to mention habituation and its pitfalls – and the power of systematic desensitization.

What not to do is equally important as what to do, as an animal trainer.

Then I started really considering the ethics of animal training: if there are several ways of getting behaviour, which should you choose? How will this choice impact current and future behaviour, the quality of the relationship, and the animal’s wellbeing?

I learned behaviour analysis: a scientific discipline specialized in really dissecting, understanding, and changing problem behaviour.

Then I tapped into a controversial subject, affective neuroscience: emotions and their impact on behavior. This topic really helped me predict, understand and prioritize: which behaviours are important?

Never one to shy away from controversy: my recent discovery is Animal Communication, a field that I can’t quite wrap my scientific brain around and that sets off all my Sceptic’s warning bells. It turns out that there is seemingly robust scientific evidence, including double-blind, randomized studies, that humans can communicate telepathically, including with animals – and learn what ails them.

I realize that for some of my readers, this will be a no-brainer, and for others, the same alarms will go off.

Quantum physics seem to be able to explain these findings, and I’m ambivalent and intrigued.

I encourage an open mind when exploring these topics: you might learn something useful to you – and the animals in your care.

I’m always learning – how about you?

About the Author

Karolina Westlund helps pet owners and people working professionally with animals to get happier, reasonably well behaved animals that thrive in the care of humans. She teaches animal behaviour management through blog posts, the odd Facebook live session or webinar, as well as more extensive online courses. She is an associate professor of Ethology at Stockholm University, Sweden and sometimes publishes scientific articles related to enrichment, animal training, and wellbeing.