Barks Blog

7 Ways to Get Behaviour

Guest Post by Karolina Westlund Ph.D

There are two important questions to ask before teaching an animal a new skill.

In another blog post, I discussed the first question, one that is extremely basic but often overlooked: “what is the cost/benefit of the behaviour”. Is it useful, useless, abuse or an ethical dilemma?

Once a behaviour has been found to be useful, it’s time to consider how to best go about teaching it.

The second question.

Which is the best technique to teach the animal how to perform a new skill?

You know the old saying “All roads lead to Rome”..?

With regards to animal training, the same is true. There are many ways to teach animals what you want them to do.

Some trainers may say: “this is how you train your dog to sit.” Or your horse to load in the trailer. Or your parrot to step up.

Many novice trainers don’t realize that what their guru is teaching is but one way out of several. And perhaps it’s the best way. The most efficient. The fastest. The one that facilitates future learning.

Or perhaps it’s not.

Perhaps it’s just what that particular trainer was taught. And that trainer’s predecessor. And so on.

What bothers me with this way of learning about animal training is not that inefficient techniques get maintained. That’s unfortunate, but not alarming.

To me, it’s the fact that unethical techniques get perpetuated that’s really disturbing.

Like the use of prong collars for dogs.

Doesn’t that look a bit like number 21 in “the 25 most brutal torture techniques ever devised”?

Do I have a problem with this type of collar? Yes, I do.

Will I go on a rant? No, I won’t.

I’ll stay detached. Though I did write a blog post about the dangers of dog collars a while ago.

So, I won’t rant.

For now. But beware of ranting below – I’ll give fair warning though.

Back to the prong collar. This device was designed to keep dogs from pulling on the leash. It accomplishes this by providing discomfort and pain when the leash is taut. So, pressure on the leash is uncomfortable or painful, and the dog will avoid it.

Actually, as long as he’s doing anything but pulling the leash taut, he should be “safe” – whatever prong collars feel like when pressure isn’t applied. Don’t know, I’ve never tried one of those – they’re forbidden in Sweden. But Grisha Stewart tested one in this video, and said they’re uncomfortable / painful even when there’s no pressure on them – and that the presence of fur doesn’t reduce the sensation.

On a walk, the dog might be behind, in front of, to the left or to the right of the person. As long as the person doesn’t jerk on the leash, all these positions would be equally acceptable to the dog – and the dog would have no further information about whether any of these positions would be preferable to the person walking the dog.

When the dog performs an undesired behaviour, something nasty happens, so the dog stops doing the unwanted behaviour in order to avoid the aversive stimulus.

That is actually the modern definition of punishment. In semi-technical terms, pulling is punished. In fully-technical terms, pulling is positivelypunished.

Punishment is a useless way to get behaviour

Punishment is a lousy way to teach desired behaviour. By definition, it only teaches the animal what not to do – any number of different behaviours can stop the aversive stimulus. Punishment has a huge list of unwanted side effects too.

Do I have a problem with punishment? Yes, I do.

Will I go on a rant? No, not yet.

I’ll just drop this topic for today. Though I did write about the 20 problems with punishment here.

You want the dog to walk nicely by your side when you go for a walk?

You need to communicate this to your pooch.

Don’t use punishment when he doesn’t do what you want. As strange as it may sound, “stop pulling” is not what you should be communicating.

Rather, reward him when he does what you want. “Walk next to me” is the message you want to convey.

To get desirable behaviour, we need to focus on reinforcement.

Wanna get behaviour? Use reinforcement!

There are several ways of getting behaviour through the process of reinforcement.

The key to reinforcement is giving the animal something he values – contingent on the desired behaviour. You reinforce when the criterion for that behaviour is met. He will then repeat the behaviour in order to get more of whatever you’re offering that’s valuable.

For instance, say you want your… cow-dog… to lie down on a towel.

Reward her for doing it –and she’ll do it more. This is what reinforcement is all about. It renders behaviour more forceful. Re-inforces it. Behaviour becomes stronger, more intense, more frequent.

Actually – technically, we’re not giving rewards, we’re giving reinforcers – because of the effect that they have on behaviour. Rewards may sometimes reinforce behaviour, but sometimes not.

If you’re not seeing behaviour change, you are, by definition, not using reinforcement.

OK, great – but let’s say that the cow-dog isn’t on the towel?

How do I get her there so I can reinforce her in the first place?

So, how do you get from what-you-have to what-you-want?

Actually, there are a bunch of different ways.

Again, don’t punish your cow-dog for not doing what you want. Rather, communicate what you want using one of these 7 techniques. As you’ll see, I like some better than others.

Seven ways of getting behaviour.

Generally, it’s important to choose a good, comfortable learning environment and set it up so that it’s easy for the animal to learn the intended response. Minimize distractions. Choose reinforcers carefully.

Here’s an extremely condensed summary of how to use the main operant techniques. Some techniques work well in some contexts but not in others – and may be used in different ways than what’s described here, although it’s beyond the scope of this blog post to go into the details.

Also, I’m just discussing how to “get” the behaviour, not how to maintain it or put it on cue. That needs to be considered too…!

Shaping:

- Reinforce a response that the animal is already offering

- Behaviour will change as the animal tries to figure out exactly what earns reinforcement

- As behaviour changes, slowly shift the criteria towards responses resembling the goal behaviour

- Gradually stop reinforcing “old” responses

Targeting:

- Present the animal with an object (what animal trainers call a target)

- As the animal reaches out to investigate the target, reinforce

- Repeatedly reinforce the animal for touching the target in the same location

- Present the target in a new location (this is called generalization)

Luring:

- Show the animal food – slightly out of reach – the animal moves to eat it

- Repeat – present food slightly out of reach, allow the animal to move and eat

- Present and move the food item to move the animal in the direction that you want

- Beware of frustrating the animal by moving the food item too far without allowing access

Scanning/Capturing:

- Observe your animal carefully (scanning)

- Don’t stare, which might be disconcerting

- When the animal just happens to perform the desired response, reinforce it (capturing)

- Wait for the animal to repeat the response that just earned reinforcement – reinforce again

Mimicking / Social learning:

- Cue another animal (the model) to perform a familiar response – in front of the learner. Reinforce. Then give the same cue to the learner – again, reinforce the response

- Ask the model for another familiar response, then cueing the learner for the same one

- Cue and reinforce the model for performing the behaviour that’s unfamiliar to the learner

- Give the unfamiliar cue to the learner and hope that he’s understood the game – reinforce it, even though it may look crappy initially. You’re reinforcing “copy your friend”, not just “perform the right response”

Moulding:

- Manually form the animals’ body into the position that you want using for instance your hands

- If the animal likes body contact and relaxes into position, keep touching and stroking (positive reinforcement)

- If the animal dislikes body contact or is tense, remove your hands (negative reinforcement)

Releasing pressure (a type of negative reinforcement):

- Give the intended cue and give the animal a gentle but firm static push (the “pressure”)

- As he starts to lean away from the pressure (an escape response), release the pressure

- Keep giving the cue immediately before adding pressure

- Allow the animal time to respond to the cue without having to add the pressure (to get avoidance rather than escape)

The elephant in the room.

I know you’ve been waiting for it – and here it is:

The Rant.

It covers the following section, and is a bit too technical for beginners, perhaps. Skip to the next section if you’re not consumed with curiosity.

I should warn you that when Ranting I often revert to my scientific background rather than becoming foul-mouthed. So, expect 3-4 syllable words and bureaucratic sentences.

Here we go.

I was hesitant whether to include pressure-release (a type of Negative reinforcement) on this list. It’s a problematic technique, but exceedingly commonly used – especially among non-trainers.

I could have just omitted it.

Instead, I chose to include it. Why?

- Negative reinforcement is arguably the most misunderstood term in the whole of psychology: many animal trainers don’t even know how to define it. I have the data to back up that statement, in case you’re wondering.

- Negative reinforcement is often used unknowingly, so many animals are inadvertently exposed to it.

- It’s got a bad reputation so nobody hardly talks about it, or teaches how to do it properly.

- I see negative reinforcement misused very badly – probably because of this ignorance.

And who is suffering because Negative Reinforcement isn’t discussed?

The animals, that’s who.

So, animals suffer, because animal trainers don’t teach about, or discuss, negative reinforcement.

Negative reinforcement is the elephant in the room.

It’s big, it’s awkward, it’s knocking over all kinds of furniture and expensive ornamental vases, and many trainers are looking the other way, saying “I only use Positive reinforcement – I wouldn’t ever stoop to that!!”

I agree that positive reinforcement is the best way of training animals.

But we don’t help animals by not talking about negative reinforcement.

I’d even go so far as to say that not discussing it is a disservice to animals, pet owners and animal professionals.

So, I think animal trainers have the obligation to discuss negative reinforcement training. At the very least so that people come to realize that they are perhaps unknowingly using it – and learn to minimize its potential harmful effects.

Here are my two major concerns when seeing how negative reinforcement is commonly applied:

- People use way too aversive stimuli – frightening animals into a flight response rather than teaching them to move away from pressure. “Pressure” can be anything from gentle touching, to presenting a toy crocodile, to shouting, waving arms and spraying water. I see people unnecessarily going for the big guns right off the bat.

- People don’t remove the pressure when the animal starts responding. This implies punishing the correct response.

Remind me, what term did I use, again, when discussing punishment of unwanted behaviour as a learning tool for teaching new behaviour? “Crappy” I think. “Lousy” comes to mind, too. Or perhaps it was “Inferior”?

That was when punishing the unwanted behaviour.

But punishing the correct behaviour?

That’s … Exasperating. Not to mention unnecessary and potentially abusive. One reason I’m ranting.

One reason animal trainers need to talk about Negative Reinforcement.

I’ll try to stop ranting now. After all, this is “7 ways of getting behaviour”, not “Pontificating about what Animal trainers should be teaching”.

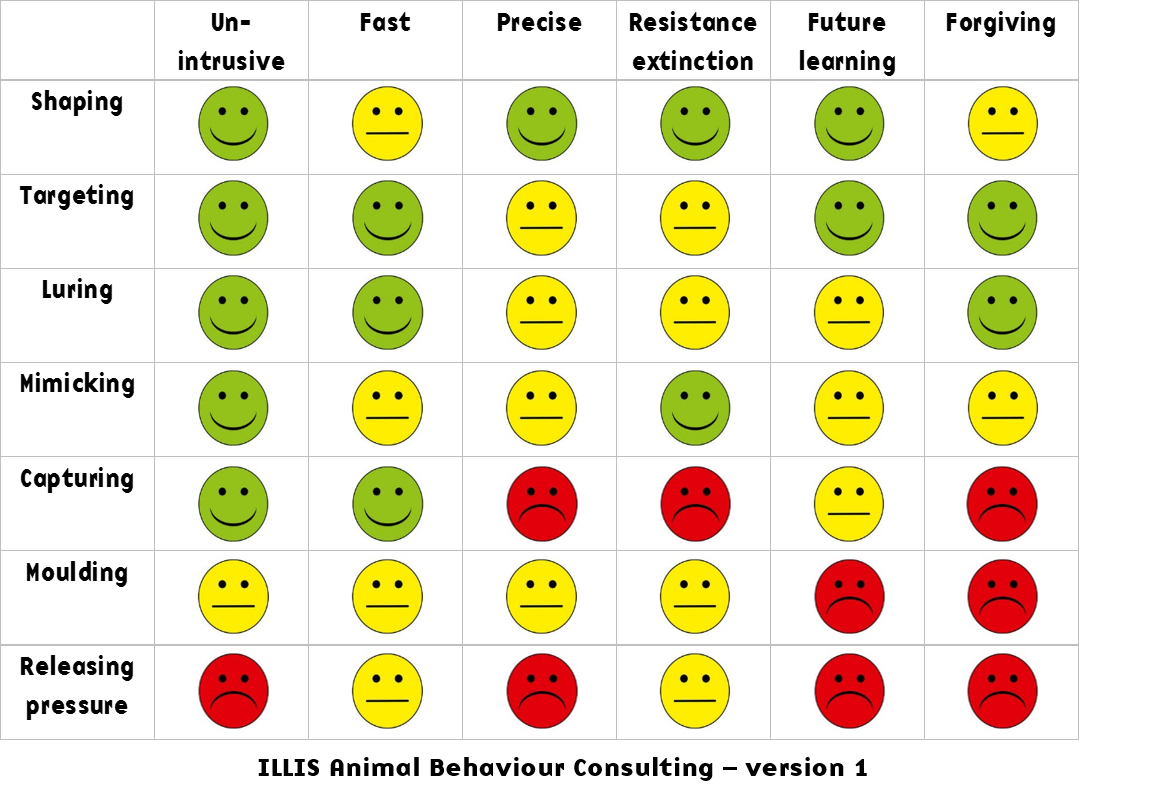

Considerations when choosing technique

The road you choose when getting behaviour can be more or less:

- Un-intrusive. How much control does the animal have of the learning and performance? Does he have choices? Is the technique potentially aversive to the animal? Will it impact the quality of the relationship? This, to me, is the single most important factor when deciding what technique to use. I realize others may prioritize differently, though.

- Fast. How quickly does the animal become proficient when learning the behaviour? How many repetitions does it take until the goal behaviour is shown?

- Precise. If you were to take pictures of the animal performing the newly learned behaviour several times, to which degree would they be similar? How close to the final goal can you get using only that technique?

- Resist extinction. How quickly does the newly acquired goal behaviour fall apart if you for any reason can’t provide reinforcement?

- Future learning. Has the animal learned something that will make future learning, using the same or other techniques, easier? Is the animal savvier? Does it understand the “training game” – and is it willing to play it again?

- Forgiving. If you make a mistake during the initial training stages, will this slow down or muck up training this behaviour – or future behaviours?

Skilled trainers often combine these techniques, thereby avoiding some of the downsides of using a single approach. In fact, the table below is probably completely useless to a skilled animal trainer, because they generally don’t perform the “pure” versions of these training techniques. They mix and match. Also, one hallmark of a skilled trainer is flexibility: the mix of techniques will depend on circumstance.

For a beginner, though, combining these techniques might be difficult, and it’s useful to know how they compare when using “pure” versions of basic techniques. So, if you’re serious about learning about animal training, I recommend that you master these techniques – and learn in which contexts they are useful. This blog post doesn’t cover even half of it, but it’s a starting point.

As seen below, there are many reasons to gear your training to positive reinforcement.

I’ve been debating with myself whether I should actually include this table, since the little happy and grumpy faces imply that there’s solid data behind these.

There’s not. What’s even worse, I am biased – so I’ve likely been unjustly harsh on methods that I dislike or am less familiar with. Also, a skilled trainer may use these techniques in a way that tweaks a certain procedure so it’s actually better than portrayed here. And an unexperienced trainer may do the opposite.

But I really liked the idea of smiley faces illustrating this concept – so I included it anyway.

Ha!

That’s the perks of publishing on a private blog rather than in a scientific, peer-reviewed journal. Not only can I go off on a rant, but I also don’t have to back up every single one of the smiley faces with data. I can be speculative.

But.

Regardless of whether the smiley faces all have the right colour, or even if we should make these relative comparisons at all, the important take-home is really to look at how your choice of training technique affects your animal given the place you’re currently at.

Keep in mind that other factors will also influence how useful the chosen technique is, such as:

- Your skill level with each technique.

- The species you’re working with.

- The animal’s prior learning.

- How well you set up the environment before starting.

- The complexity of the behaviour you’re training.

- Your timing.

- The value of the reinforcers.

- Where reinforcers are delivered.

- The interval between repetitions.

- And so on…

Still, I’m arguing that irrespective of these other influential factors, there are some innate differences in how these techniques tap into the animal’s learning mechanisms. All else being equal, outcomes should be slightly different if you’re going with just ONE technique.

Which road will you take – and how can you shift it towards “greener smiley faces”? Let us know in the comment’s section, below!

Interested in learning more? Check out my website.

Reading list:

Fugazza et al. (2015). Social learning in dog training: The effectiveness of the Do as I do method compared to shaping/clicker training.

Hendriksen et al. (2011). Trailer-loading of horses: Is there a difference between positive and negative reinforcement concerning effectiveness and stress-related signs?

Innes & McBride (2008). Negative versus positive reinforcement: an evaluation of training strategies for rehabilitated horses.

Santos (2009). Limitations of Prompt-Based Training.

Sdao (2008): Advanced Clicker Training (DVD).

Zeligs (2014): Animal Training 101.

About the Author

Karolina Westlund helps pet owners and people working professionally with animals to get happier, reasonably well behaved animals that thrive in the care of humans. She teaches animal behaviour management through blog posts, the odd Facebook live session or webinar, as well as more extensive online courses. She is an associate professor of Ethology at Stockholm University, Sweden and sometimes publishes scientific articles related to enrichment, animal training, and wellbeing.